This article was written by Lula Chen, Lily Tsai, and Alisa Zomer for Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) available online.

Partnerships between academic researchers and implementing organizations produce opportunities for both parties to advance shared interests, learn about their own areas of expertise, and add to the growing network of individuals and institutions dedicated to using rigorous research to inform program design. For researchers who conduct field experiments, research partnerships can enable randomized experiments in real world settings and can thus speed scientific learning while enhancing public welfare For implementing organizations, such partnerships can speed learning about organizational objectives both by taking advantage of the latest in research methodology and academic literature on a topic and adding a new perspective to a team, but also because academic researchers’ incentives involve peer reviewed publication and fairly rigorous transparency practices –- all of which add up to evaluations and research designs, which, in principle should provide more actionable information to a NGO or government.

There is no set way to identify, enter into, and conduct a research partnership. There are, however, lessons learned from previous partnerships. These lessons have led some organizations to standardize the process through which they engage academic researchers as partners. The following summary is part of an ongoing series on Academic/Practitioner Partnership Models. In each entry, we lay out the structure of one organization’s model for engaging in research partnerships, discuss the choices made in devising that model alongside the reasons for doing so, and outline the lessons learned from the implementation of the model.

As with all models, there is room to improve. We continue to experiment with a range of possible improvements and experimenting with group and collaborative learning in addition to strong bilateral partnerships. Feedback is welcome mitgovlab@mit.edu.

Model: MIT Governance Lab Engaged Scholarship Model

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Governance Lab (MIT GOV/LAB) is a research group and innovation incubator that aims to change practices around corruption, government accountability, and citizen voice. One part of our mission is to produce and promote engaged scholarship, which we define as rigorous research that is co-created by practitioner organizations and grounded in the field, thus increasing the probability that practitioners will make use of the insights and evidence arising from the collaboration. Because the rigor of research alone is not enough to ensure uptake of findings, our engaged scholarship model is based on values of equitable exchange and respect between practitioners and academics.

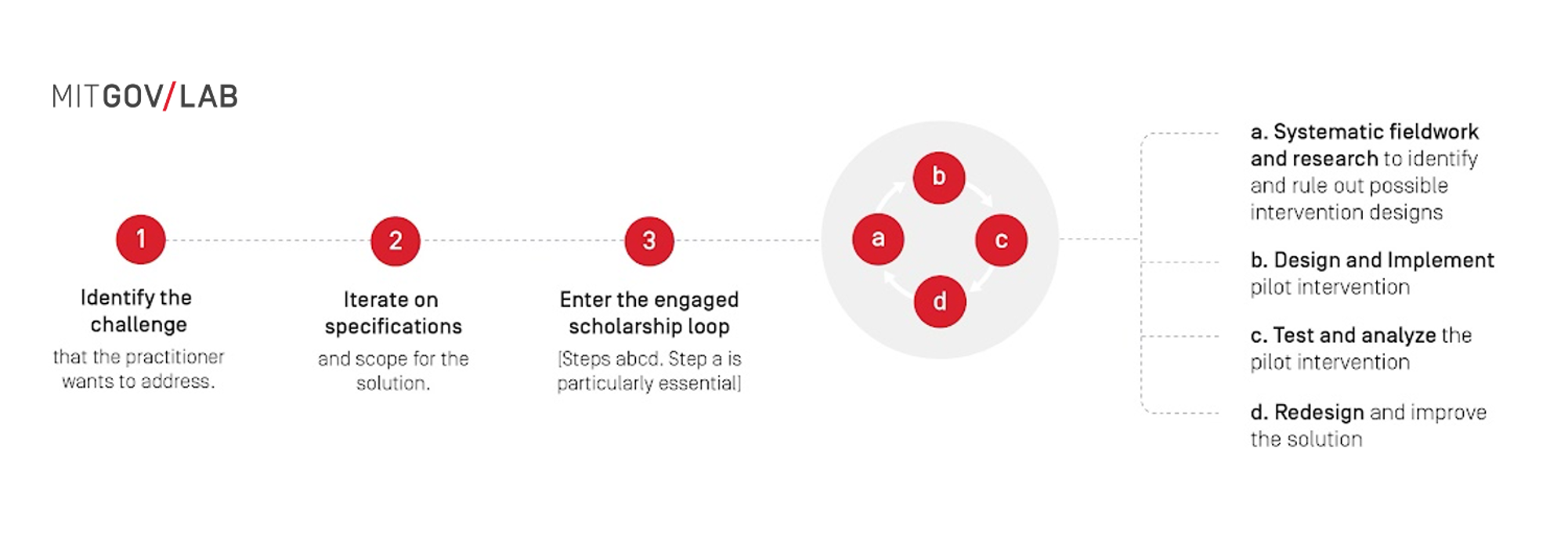

We focus on sustained, multi-year, and multi-project partnerships between academics and practitioners working iteratively to identify questions that are important to answer and solutions that are important to test. Our approach produces research and evidence that help practitioner organizations make operational decisions as well as provide general knowledge to the larger field. We are committed to fieldwork, and draw on theories and methodologies from a variety of academic disciplines and subfields. See below for a working illustration of our model.

Figure: MIT GOV/LAB Engaged Scholarship Model

What is in the Engaged Scholarship loop?

The key element in our model is the Engaged Scholarship loop. The Engaged Scholarship loop is based on a classic engineering loop of ideation, prototyping, testing, and redesign. In this loop we introduce both rigor and equity: rigor in the range and relevance of the methodologies applied, and equity in the continuous, structured dialogue with practitioner partners on the choices made as we travel through the loop.

a. Systematic fieldwork and research to identify and rule out possible intervention designs. The goal in this step is to scope out the parameters of the project. These parameters can include 1) the target population, 2) the modality of delivering the intervention, 3) the time constraints of the intervention, 4) the political and social constraints of the intervention, and other relevant issues. Collaboration at this point might include systematic field research to collect facts, stories and descriptive data as well as analysis of existing administrative and survey data in order to analyze the context, the target population, and the political economy of the problem. It may include looking at the existing evidence base for relevant solutions, and learning from history and other countries. Using existing theories and drawing from multiple disciplines to reason about which ideas are likely to work and which are likely to fail, given the context and political economy, can also be useful here. Collaborative research between practitioners and academics, especially in-depth fieldwork to understand the context and perspectives of people on the ground, is crucial at this point, although it is often overlooked and underappreciated in quantitative research. We recommend making this step as collaborative as possible between the academic and practitioner side, with the practitioner side providing direction for the scope of the project.

b. Design and implement pilot intervention. In this step, the goal is to design and implement a pilot intervention, developed between practitioners and academics, that takes into consideration research findings from step (a). We recommend letting the practitioner side take the lead in designing the intervention itself, with advice from the academic side, because the intervention has to be consonant with their mission and capacity (see our guide below on how to navigate these conversations). There are important opportunities for academics to contribute to the design by working with practitioners to articulate, clarify, and refine their theory of change for the selected intervention. Academics can also help practitioners learn by co-designing short feedback loops to allow for reflection and mid-course corrections.

c. Test and analyze the pilot intervention. In this step, the goal is to evaluate the pilot intervention that was developed in step (b). Results from the evaluation should be integrated into the design of the intervention and full study design (for example, determining when and how data are collected or in the selection of who participates in the intervention).

Collaborative research at this stage can help assess whether the pilot intervention had the short- and medium-term impacts that the intervention’s theory of change posited, and why it may have failed or succeeded, whether the intervention may have affected different groups differentially, and whether there were unanticipated consequences. The results of research at this step determines the next step in the process. Should the solution be implemented and evaluated at scale? Or, should the solution be redesigned and improved? After agreeing to the goals and scope of the research, we recommend letting the academic side take the lead in conducting the evaluation, with insight provided by the practitioner side.

d. Redesign and improve the solution. In this step, the team works together to review steps (a-c) and make changes or tweaks to develop a stronger intervention. Repeating the loop at this point provides a focal point for building productively on what practitioners and academics have learned from the failures and successes of the previous iteration. Continuing with another iteration strengthens the relationship and builds capacity for the synthesis of lessons learned and the coherent accumulation of knowledge and evidence.

Project Examples and Lessons Learned

Below is a selection of engaged scholarship projects with practitioner partners to demonstrate the model’s outputs. In addition to developing applied outputs in the form of research briefs, we also aim to write learning cases to document challenges and outcomes of the partnership itself, including how we traversed the engaged scholarship loop in the model.

- Rapid Survey to Inform Covid-19 Response in Sierra Leone. In this project designed at the outset of the pandemic, we partnered with a local research and policy group as well as government agencies in order to ensure research was useful, and also that results would be taken up by relevant decision-makers. Results from our collaborative research helped to inform the design of the second lock-down in Sierra Leone. (See our research brief, trust outcomes, and lessons learned.)

- Examining the Impact of Civic Leadership Training in the Philippines. Through qualitative fieldwork in the Philippines, we adapted the research based on pilots our partners had done previously. The research focused on community-level training of citizens and officials together and separately, and evaluated the effects of cooptation of community leaders by local officials. (See our research brief and learning case, and longer research report.)

- Testing Access to Information in East Africa with Mystery Shoppers. We conducted fieldwork to figure out the target populations and what modality was best for delivering the intervention to understand the following questions: how should ordinary citizens in Kenya make requests for information about local service provision and government performance? With our partners we field-tested several iterations of a mystery shopper experiment to better understand the ordinary citizens’ experience requesting information from their local government. (See research brief on results from Kenya, Tanzania, and learning case on the partnership model.)

- A Novel Approach to Civic Pedagogy: Training Grassroots Organizers on WhatsApp. We collaborated with Grassroot, a civic technology organization based in South Africa, to pilot and evaluate a course on leadership development for community organizers taught over WhatsApp, one of the world’s most popular messaging apps. This project has many iterations in the engaged scholarship loop, especially in refining the research question and adapting the intervention through focus groups, on- and offline simulations, and observed behavior. (See our research brief, learning case, and guide to teaching on WhatsApp.)

Strengths and Challenges of Engaged Scholarship

Our model has a number of important strengths:

- Building multiple, meaningful interactions throughout the collaboration. In our model, we integrate the uptake of research into multiple points of the model. Knowledge is produced in collaboration between practitioners and academics throughout the process, and the insights feed into subsequent stages and iterations of the collaboration.

- Identifying locally relevant research questions to improve uptake. Because practitioners identify the problem they want to solve, and work with academics to brainstorm possible solutions and identify important research questions, the research that is produced is by definition relevant to their work and specific to their context.

- Building trusted partnerships. Because this model involves sustained collaboration and interaction between academics and practitioners through multiple cycles of design, research, and learning, there is ample time and opportunity for partners to get to know each other, to learn from one another, and to build trust. Partners know from the outset that the process is a “repeated game,” so they are more likely to have more trust in each other from the outset. More trust translates into more openness to innovation and iteration, and opens up the possibility of meaningful learning from failure as much as from success.

- Using a diverse research toolbox to increase the salience of research and practice to citizens and communities. Our toolbox includes ethnographic research, case studies and process tracing, survey data collection, administrative data, as well as survey and field experiments. The range of methods and the close involvement with practitioners and communities means that the questions we ask and the evidence that is produced reflect the knowledge, experiences, and perspectives of ordinary citizens and communities.

Challenges of the model include:

- Building trusted partnerships takes time and resources. In research, and especially in times of crises like the pandemic, it’s hard to develop new partnerships with deep trust in a short amount of time. This approach requires time and resources, including flexible core support, to allow organic collaborations to develop. At the same time, our model, which has relationships grounded in equitable exchange at its core, is designed precisely for long-term collaborations and with resilience to take on unexpected changes.

- Balancing impact and outside influence. Engaging the right mix of stakeholders within government and the development community (local and international) with good user research and design is critical to producing solutions that these stakeholders will take up and use. We aim to produce policy and academic outputs for each project, as we are trying to balance the opportunity to work through inside channels to get our research in front of high-level decision-makers with being part of the more traditional research circles that seek to influence policy from the outside. However, we acknowledge that this balance is not always feasible and we sometimes must focus on either policy or academic outputs.

- Allowing for flexibility. Partnership-centered approaches means that we have to be flexible about the issues and questions, because what’s relevant for our long-term partners can rightly change over time. Being flexible, however, can be challenging to develop and execute a rigorous research design and can impact the ability to say something meaningful or useful about the results to guide practitioner decision-making.

- Our How to have difficult conversations guide also details challenges of academic-practitioner collaborations, including aligning incentives, expectations and timelines, decision-making and team buy-in, and balancing learning and dissemination. The guide also includes practical suggestions on how to navigate these tensions.

Going Forward + Engaged Scholarship Resources

In addition to using engaged scholarship in our work, we are also interested in producing public goods —guides, tools, and case studies— to support others interested in exploring engaged scholarship in their own contexts and relationships.

- How to have difficult conversations. As referenced above, we developed a practical guide for engaged scholarship with recommendations on how to strengthen and improve academic-practitioner research collaborations (see also EGAP’s methods guide on 10 Conversations that Implementers and Evaluators Need to Have).

- Risk and Equity Matrix. An exercise for practitioner-academic research teams to systematically consider potential impacts for the range of actors involved in the research process.

As with all models, there is room to improve. We continue to experiment with a range of possible improvements and experimenting with group and collaborative learning in addition to strong bilateral partnerships. Feedback is welcome mitgovlab@mit.edu.