Below we include some excerpts from the guide, including the preface, executive summary, and introduction. Download the complete guide in English, Spanish or Japanese for all the details. The “Don’t Build It” guide was featured in MIT News by Will Sullivan. The guide was also featured in posts by Tiago Peixoto on DemocracySpot, Koketso Moeti in iAfrikan and the World Economic Forum, Rustam Khan in The Tech, ICTworks, and by Lwazi Maseko for the Civic Tech Innovation Network. Luke served as the keynote for Code for Japan Summit in 2022 (check out this video of his remarks).

Preface

This guide is for teams or managers involved in considering or building “civic technology”, i.e., technology that helps people engage government more effectively. It is the distillation of my four years spent building Grassroot, a civic tech platform in South Africa.

The guide is focused on the practical. I have chosen the topics by reflecting on what people have asked for advice on over the years; on what I wish I knew when I started, or on what early advice to me was most valuable; and on some of the things that went wrong along the way.

Since software provides in itself no guardrails against building what should not be built, an organization or leadership team needs to develop its own precautions. But that is very hard when all around you people are pretending to build cool new apps and one article after another is talking breathlessly about supposed “technology for good”. As proof of these forces, we can observe that for half a decade, one research report after another has pointed to the limited effect (if any) of well-intentioned but insufficiently rigorous technology projects (“let’s build an app!”). And despite all of that research, the apps keep being built.

That brings you to my motivation for writing this guide. I believe that technology can help ordinary people build power and make the state more accountable and responsive. I believe that, when targeted at the right problem at the right time, it can make an enormous difference. I’ve also seen close-up how the forces of contemporary thought, funding and status will push you towards building what should not be built, with teams who don’t know how to build it. You’ll notice the tone isn’t typical of academic how-to guides—my approach is to describe the process honestly and realistically, with hopes that it will give people a better sense of what “building an app” entails, and how they can do it well, or (better yet) not do it in the first place.

The guide starts with project selection, including why the best project to select is no project at all. It moves on to team structure, and the extreme importance of a full-time senior tech lead (or chief technology officer (CTO), understood as an excellent engineering manager). It then covers timelines, emphasizing shipping early but having enormous patience getting to maturity, above all in finding product-use-fit, and avoiding vanity metrics. The guide then goes into some detail on hiring, covering the CTO role, senior contractors, designers and young engineers.

The longest section, by some distance, is that on hiring. Hiring is the one thing considered critical in every piece of the lore, by founders and investors and managers alike, across all sectors. It is also the field in which I think I got it mostly right, and for reasons I can explain in ways that I believe will be helpful.

Executive summary

If you just remember these…

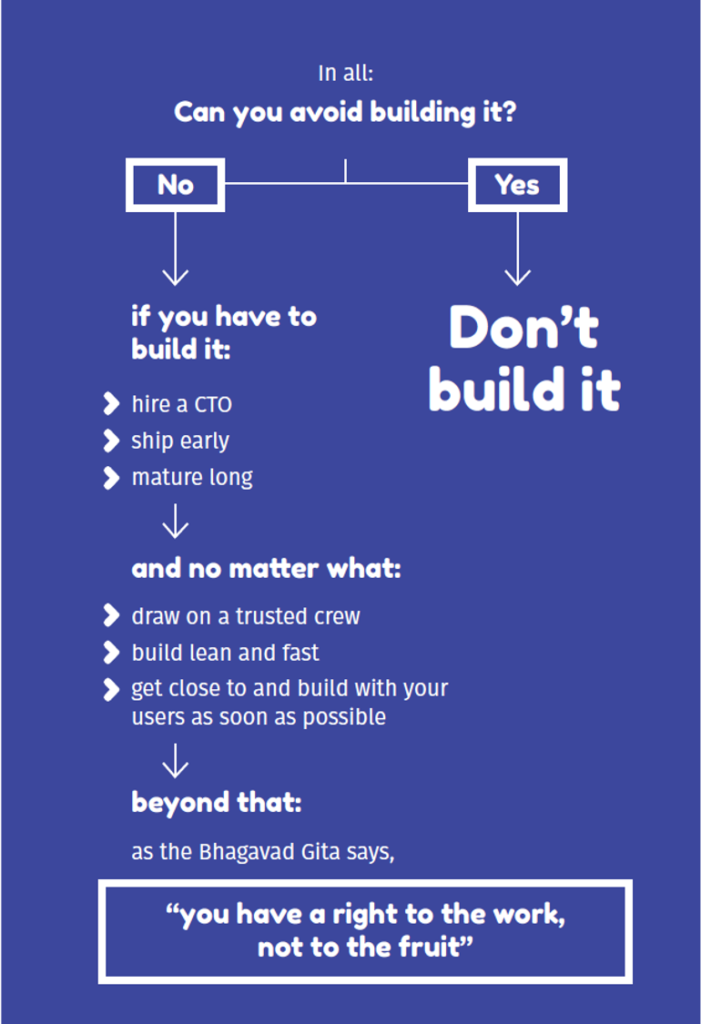

If you can avoiding building it, don’t;

if you have to build it,

hire a chief technology officer (CTO),

ship early, and mature long;

and if you can’t do that (or even if you can),

draw on a trusted crew,

build lean and fast, and

get close to and build with your users as fast as possible.

And if you have to, some other tips:

- Outsourcing is great as a tactic, but a terrible strategy.

- Add full-time talent cautiously, at cost levels where you can keep them in the team and invest in their growing skills over time.

- Get close to your users and to do so fast with a dedicated community engagement team. Adaptability and speed of learning are core criteria in every role.

- Set a budget that gets you off to a quick start, but allows you to keep iterating over time.

- Tech principles: stick to open source and pick a popular language.

- Nothing is more important than rapid early learning, and vanity metrics short-circuit such learning.

A rule for this sort of guide is never give specifics that people can hang around your neck. A rule for software development is “it takes as long as it takes”. I’m going to break both rules, and say that for a good team of 3-4, following good practices, you should be able to ship a moderately complex product in about 3 months, and get it to some form of stability and maturity within 12 months. After that, of course, you start again—if you have users. If you don’t, stop at 6 months, or better yet, 4 months, or best yet—don’t build it.

Does this project need to happen? Probably not.

The central problem of software is that anything can be built. With a physical structure, nature and physics puts some constraints on the space of ideas. With software, a project can be wholly completed and deployed and only then reveal itself as fundamentally flawed, and then we are all so inured to bad technology that no one will really notice. Construct a monstrous building in the middle of nowhere and movies might be made about you; build a pointless app that no one uses and you will just need to cite a misleading metric in a donor report and no one will care. Conversely, construct a good building in a sensible place and no one will think it worthy of notice; build a not-terrible app that people use for longer than the launch press release circulates, and you will immediately be nominated to half a dozen “X under X” lists.

So, by far the best method is to adopt a simple principle: Don’t build it.

When someone says, “We should build some tech for that”, just say no. When an investor or donor says, “Why don’t you build some technology”, just say no. When you read another article or see another TEDx talk about someone pretending their app achieved something, while citing numbers that are both unverified and meaningless, and a voice inside says, “why don’t we also build technology”, just say no.

Does that mean that the rest of this guide is pointless? Hopefully so. But in reality, at some point some idea may gather such momentum or such force of conviction that the “do not build it” ethos will start to falter. At that point, ask these questions:

Are people already trying to do what the technology is supposed to help them do?

If yes, how are they doing it now, and are you sure you know why that does not work? And why will technology make any difference to the reason their existing attempts are frustrated?

If not, why would having technology make a difference? Why would someone who did not want to do X now want to do X just because some tech exists to do it?

Of course, it is easy to fake answers to such questions in a way that justifies building something, and that will happen most of the time. But suppose they are answered honestly and it turns out that, for example, people are trying to do whatever the technology is supposed to do, and it is not working because of some fundamental problem.

The strong temptation will be to immediately try to use technology to work on that deeper problem. But, again, don’t build it! First ask the questions above about this fundamental problem you’ve discovered. For example, before you build a piece of software to help a government know about a phenomenon (violence, or service outages), ask: Aren’t people already trying to tell them about this? If they are being ignored, why are they being ignored? If it’s because of power imbalances, will your well-meaning alert technology really do anything about that? Or might it be irrelevant, or even worsen the problem by allowing the powerful to pretend (to themselves and to other elite stakeholders) that they are doing something? If no one is attending government meetings, is that because they don’t know about the meetings, or because when they attend no one listens to them? Such examples could be multiplied almost endlessly.

If, after all of this not-building, you come to a problem where it is very clear that a) people are trying to do whatever the tech is supposed to let them do, but it is not working; and b) it’s not working primarily because of some problem that technology can address; and c) the grounds for this are clear and certain… then it might be time to start considering possibly building something.

But probably still not.

Ok, hopefully we’ve convinced you to check out the full guide for more details and recommendations on:

- Hiring and contracting

- Timelines and budgets

- User vs. vanity metrics

- Technology

You can download the guide above. But for now, we’ll provide a teaser on the ending…

___

Suggested Citation: Jordan, Luke. 2021. “Don’t Build It: A Guide For Practitioners In Civic Tech / Tech For Development”, Grassroot (South Africa) and MIT Governance Lab (United States).

About: Luke Jordan is the Founder and CEO/CTO of Grassroot, a civic technology organization based in South Africa, and the 2021 practitioner-in-residence at the MIT Governance Lab. Contact: luke.jordan@grassroot.org.za.

Thanks to the entire Grassroot team for suffering the lessons learned in the guide, including Katleo Mohlabane, Busani Ndlovu, Mbalenhle Nkosi, March Ratsela, Zinhle Miya, and Paballo Ditshego. And, thanks to Tiago Peixoto, Arjun Khoosal, Lily L. Tsai, Alisa Zomer, and Maggie Biroscak for providing input into various versions of this guide. Many thanks to the ILDA team for the Spanish translation and Kazuki Imamura and the Code 4 Japan team for the Japanese translation. Illustrations and graphic design by Susy Tort and Gabriela Reyagadas.