Suggested Citation: Zomer, Alisa, Luke Jordan, and Kelly Zhang. 2020. “A Novel Approach to Civic Pedagogy: Training Grassroots Organizers on WhatsApp.” Draft Outcome Brief: Grassroot (South Africa) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Governance Lab (United States).

Our guide on how to teach on WhatsApp and course materials from the pilot are also available online. Below we include some excerpts from the research results:

Summary

Grassroot, a civic technology organization based in South Africa, launched a first-of-its-kind leadership development course over the messaging platform WhatsApp. The distance-learning course, Leadership through Storytelling, was designed to build the capacity of organizers for sustained community activism. In 2019, Grassroot piloted the course and collaborated with the MIT GOV/LAB to conduct mixed-methods research on the effectiveness of the course content and its potential to advance long-term community organizing goals. This Outcome Brief discusses pilot results and the possibility of reimagining social media platforms such as WhatsApp, often in the spotlight for their negative role in spreading misinformation and sowing the seeds of distrust, as a new avenue for advancing civic pedagogy and networking for long-term social movement building. Though additional iterations are required, initial results suggest that the WhatsApp course was able to connect grassroots organizers in a novel way that encourages learning and information exchange.

Background

Grassroot, a civic technology organization in South Africa, created a messaging platform to help grassroots leaders communicate more effectively with their communities. While the Grassroot platform supported increased levels of activism (e.g., more meetings, petitions, actions), there was a steep dropoff in community engagement after an initial spike. From engaging with communities, Grassroot believed that existing methods of leadership development —primarily political education through inperson workshops— needed to be supplemented by new material and delivery methods. Communities were more fragmented than in the past, less easily unified around a single goal (as had been the case for defeating Apartheid, for example), and potential community leaders were less likely to belong to formal organizations that could support them to attend multi-day in-person leadership programs. This led Grassroot to develop a first-of-its-kind distance-learning course taught entirely over WhatsApp.

The course, Leadership through Storytelling, was designed to meet people where they are, engage them over a sustained period of at least a month, use group-based pedagogy, and focus on long-range leadership capacity. While WhatsApp groups are often in the spotlight for negative reasons, the platform seemed like a promising medium to test Grassroot’s objectives, especially in low-bandwidth environments. The course material drew on Harvard Professor Marshall Ganz’s Public Narrative work, which uses storytelling on individual and collective values and experiences to inspire leadership and commitment to social change. Piloted over five classes, the course reached more than forty distance learners in South Africa, largely in urban and peri-urban areas near Johannesburg and Durban.

Grassroot partnered with MIT GOV/LAB to assess the pilot and to determine which course components were most effective. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, the research collaboration found that: (i) WhatsApp is a viable medium of civic pedagogy, if combined with a strong teaching team, behavioral incentives, and attention to design details from the start; and (ii) the course content had varying effects on different demographics, including employment status and education, but likely requires substantial revision to better link storytelling to organizing tactics and strategies, including a focus on recruiting community members to engage more deeply and regularly in activism.

The overall implication, for Grassroot and other organizations, is that WhatsApp’s potential as a pedagogical medium should be further explored, specifically how to build relationships and networks that translate into offline action.

Key Takeaways

Below are three takeaways that touch on participation rates over the course of the pilot, the impact of storytelling on action, and the need to focus on deeper recruitment to build sustained social movements. Additional details on research methods provided at the end of the brief.

How was class attendance and participation on WhatsApp? Increased over time with thoughtful design, behavioral incentives, active coaching, and iteration.

One challenge in teaching a distance learning class on WhatsApp is how to maintain good-quality participation. There were multiple reasons participants would not follow through with the course: it was taught entirely online without the opportunity for in-person interaction, it was free (so participants did not feel any monetary commitment), and was time-consuming (the entire course was estimated to take 16 hours over the month).

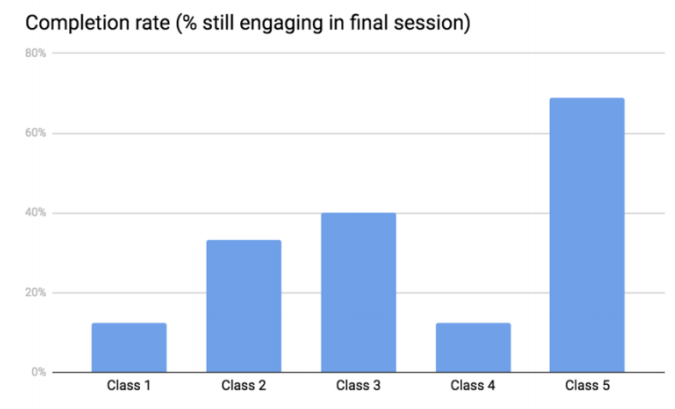

During the pilot, each group had 10-15 participants and participation rates across the cohorts varied widely. On a composite measure (see brief for details) of what percentage of questions were answered in group sessions and whether homework assignments were completed, average participation rates across all classes ranged from 16 (out of 100) to 58. On the simpler measure of how many participants answered more than a third of questions in the final session, rates ranged from a low of 12% to almost 70% (see figure). The groups with low completion rates showed that just because WhatsApp is a near-ubiquitous communications medium, using it to deliver multimedia content does not necessarily lead to participant engagement.

On the other hand, when we made adjustments to multiple course elements (course content, role of coaches, incentives for participation, and recruitment strategies), participation increased. This shows that with sufficient care and attention to detail, WhatsApp can be used to build an active, group-focused online classroom. Perhaps more so, the very high completion rates —especially in light of the obstacles to participation— show that in practice, WhatsApp can be an effective, new form of a classroom, if carefully structured and with its use repeatedly iterated. For details, see the practitioner’s guide.

Can stories from the course inspire action? Youth and the employed seem to respond more to the power of stories.

A central research question was how storytelling, as adapted from Professor Ganz’s work on Public Narrative, influences grassroots organizers. In particular, we were interested in examining if the stories used in the course were effective in inspiring people to take action or in influencing beliefs that they could enact change as an individual or as part of a group (i.e., individual or collective self-efficacy). Additionally, we wanted to tease out whether people as individuals or a group believe in their ability to take action (internal efficacy) or to change someone else’s behavior (external efficacy).

To measure this, we A/B tested two types of stories from the course. The first type were stories from the course that local organizers developed during the WhatsApp course, which were shared with their permission. The aim of this was to evaluate how effective the WhatsApp course was in helping participants to produce stories that promote political efficacy. The second type was an example story that Grassroot provided. The aim of this was to evaluate how effective the course stories were in improving political efficacy. Both were independently administered as a part of a phone survey (see example below). Here’s what we found:

- Hearing stories from the course made youth (ages 18-35) more likely to volunteer to mentor another organizer and increased perceived external collective efficacy (e.g. “If people gathered together and demanded change, my local government would take the steps to enact change.”).

- Hearing stories from the course increased internal collective efficacy for people with steady employment (e.g. “I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of the important issues facing my local area.”). In qualitative interviews, several respondents mentioned that unemployment makes it hard for people to stay engaged in voluntary activism, which seems to support the quantitative results. One respondent talked about a strategy for unemployed persons to protest for jobs, explaining that “there is nothing a South African won’t do for a job” and that once they get a job, they stop participating – “politics of the stomach.”

- Upon hearing an example story, those who completed secondary education or high school are slightly more skeptical about the ability of stories to inspire people to action. Hearing stories from the course also reduces external individual efficacy among this population (e.g. they are more likely to believe “People like me DON’T have any say about what my local government does.”).

Story from the course:

“In my community we have the problem of electricity, it happens every time when we try to use appliances like [the] heater, stove. The electricity company came to us promising to fix it by cutting off the connection because they said they needed to deal with that low supply but unfortunately, we went without electricity for some months and they never came to us for the update. This takes me back [to] when I was young and didn’t know how to raise my voice against the situation I didn’t agree with. I remember when I was employed in one of the big financial institutions in South Africa where we were supposed to use English to communicate at the place of work. We didn’t use our home language, but unfortunately others were using Afrikaans which was not allowed, and we launched a complaint. It showed my integrity as a leader and the values that I have now. I will be leading my community to go and protest against electricity that we have our electricity back. It will be a peaceful march to the offices of [the] company that supplies electricity in the municipality demanding our rights to have the electricity and this must happen now because we believe that if we don’t stand up and go this route as a community, we will suffer.” — Bongani Sibaya, Grassroot course coach

What are effective ways for online learning to facilitate long-term movement-building?

Online tools need to focus more on recruitment and networking. Grassroot’s motivation for creating the course was to first think about long-term ways to build sustained social movements, and, secondly, to do so by reclaiming social media platforms to support citizen engagement. To better understand how these objectives play out in practice, we conducted 20 qualitative interviews to understand the specific contexts in which grassroots organizers were operating. Here are some highlights:

- Based on the interviews, many organizers aren’t recruiting other community members for sustained engagement. Community members are recruited to attend mass meetings and participate in mass actions used to demonstrate power and proof of community demands. One respondent noted that a lawyer suggesting they want a minimum of 5,000 community members to be present for their case to be substantial, “if you are serious you must show people.” Another respondent said “our ultimate weapon is the community” we say to members ‘without your involvement nothing will move’ and we mean it”. Despite the importance of community, few respondents indicated strategies for deepening engagement or persuading people to join as organizers.

- A few respondents talked about using cases or specific stories when discussing issues with community members, two of whom participated in the Grassroot course. As one participant commented, “Story-telling is not difficult because members of the community all have different stories to tell about the same issues that they face.” For this respondent, who took the course, stories are used as a tool to inform the committee on how to bring about the desired changes as requested by community members through voicing their stories. This was echoed by another course participant. Another, who did not participate in the course, noted that they used stories to articulate that their situation isn’t okay and to foment hope. People get used to problems and can’t see what is wrong with them, stories can help to increase awareness in the community, to make potential futures relatable.

Discussion and Next Steps

Over the course of the pilot development and research process, we’ve made leaps in our understanding of how to cultivate social media, like WhatsApp, as a positive medium for civic pedagogy and distance learning. From interviews, we also know that the course has a fresh appeal as well as benefits from group learning. One respondent said the course was helpful and convenient, “I’ve never done anything online, so I liked it. We were also one in the group and it was a lot of fun”. Another noted that they learned lessons from the others in the course, from the strategies they use, and hearing their stories gave them hope.

Some key observations emerged from the research findings to inform Grassroot’s next steps:

- If recruitment is a focus for long-term social movement building, the course content needs to more explicitly link storytelling to engaging community members. Similarly, the benefits from sharing stories of success, failure, and hope may be a significant learning impact and course content could be strengthened to emphasize learning and to deliberately foster more interaction between participants. Given the limited emphasis organizers seem to place on recruitment, this may indicate additional work is needed to build leadership capacity first, perhaps by introducing “harder” organizing tools (e.g., power mapping, tactics).

- Data from the phone survey suggests that Grassroot might consider targeting course recruitment for youth and the employed, because these groups responded more positively to stories. This may be a result of youth being more idealistic and perhaps those who are employed are more empowered economically, both factors that could lead to increased political efficacy.

- The survey data also show that hearing stories can reduce the political efficacy of those with more education. However, interpreting these findings requires additional research to understand why. For example, one possible interpretation is that higher education makes individuals more susceptible to disillusionment, because they have knowledge as to how systemic these problems are. It could be that overcoming this type of disillusionment is necessary for the type of long-term planning necessary for sustained structural change, but further research is necessary to clarify why those with more education tend to be more easily disillusioned by stories.

Though we have just begun to explore the potential of WhatsApp for fostering stronger ties among grassroot organizers, we’re encouraged by the pilot results. Moving forward, Grassroot is continuing to iterate on the course, developing new outreach and recruitment methods, adjusting the course curriculum, and designing a new WhatsApp course focusing on organizing tactics and skills. This second course will be made available for organizers who completed the first course on Leadership through Storytelling. MIT GOV/LAB is also working on a detailed summary of the research findings and implications more broadly for building stronger social movements. For details on the pilot and the mechanics of teaching on WhatsApp, please check out our practitioner guide.

Research Methods

Grassroot and MIT GOV/LAB co-designed the research questions and process through a series of interactions, including a design sprint and four rounds of field work. In total, MIT GOV/LAB spent more than 12 weeks in South Africa supporting the following mixed-methods research:

- Focus groups (May 2019) were conducted to test initial course content in two townships near Johannesburg, including six focus groups with 4-10 people each over two days. The focus groups provided insights on how to best contextualize the course content for the target audience, including understanding how concepts were interpreted, improving the content flow, and the need to simplify academic language.

- Simulations (May 2019) took place in the Grassroot office building in Johannesburg, including a total of 18 participants over four simulations. Participants sat together in a room and completed the course using WhatsApp on their mobile phones, facilitated by Grassroot in a separate office. Participants were then asked to fill out a survey and afterwards engaged in a group discussion led by a GOV/LAB trained local research assistant. The simulation provided key lessons on how to teach over WhatsApp, such as the need to reduce the overall material, clarifying instructions, and what mix of question types work best and how often.

- Participant behavior (June – September 2019) was recorded from the pilot course through the large (12- 15-person) and small (3-5-person) WhatAspp group chats. The archived WhatsApp chats provide rich information on the practicalities of learning and teaching on WhatsApp.

- Phone surveys (June and October 2019) were conducted, including a baseline survey of 306 individuals before the pilot and an endline survey after the pilot. Individuals were selected by high-use and activity on the Grassroot messaging platform, including number of meetings called, group sizes (medium: 10-50 members or large: 50-3,000). All those who were interviewed in the baseline were recontacted for the endline survey, yielding 231 respondents. An experimental component included A/B testing stories drawn from the pilot course to assess the impact of these stories on political efficacy and civic participation. We also included a behavioral measure, where respondents were asked to text a short code or sign a petition as a measure of whether they would take an action to support a community cause.

- Qualitative interviews (October 2019) took place after the pilot to get in-depth feedback on the content and future demand for the course. Using the same list of people pulled for initial course recruitment in May (based on high platform use, tagged organizers, and smartphone use), we recruited respondents who took the course and those who did not, excluding people outside Gauteng Province. We trained two local research assistants to help conduct 20 in-depth, semi-structured interviews.

Image: Durban, South Africa (Alisa Zomer).