This article was written by Will Sullivan for the World Bank’s Global Partnership for Social Accountability. The original post is available online.

Last spring, as Covid-19 began to spread across the planet, the MIT Governance Lab (MIT GOV/LAB) teamed up with the Institute for Governance Reform (IGR) and government partners in Sierra Leone to conduct national surveys that would help develop a data-driven response to the pandemic.

As of 2017, 65% of people in Sierra Leone lived below the poverty line (less than $1.25 a day), so it was important that these surveys reached poorer citizens at risk of both catching the virus and running out of food and money during lockdowns. Many people in Sierra Leone are also difficult to contact because they have limited access to electricity and live in areas with weak phone service. The research team had to develop a plan for how to reach vulnerable people through multiple survey rounds, despite being uncertain if, when, or how the pandemic would spread across the country.

How feedback from at-risk citizens in April shaped the pandemic response

The study began in April 2020 with a round of in-person surveying. The project was led by MIT Professor Lily L. Tsai, Stanford postdoc Leah Rosenzweig and IGR, and was planned in partnership with Sierra Leone’s Directorate of Science, Technology & Innovation, the Ministry of Finance’s Research & Delivery Division, and Statistics Sierra Leone.

There were only a few dozen confirmed cases of Covid-19 nationwide at the time, and the field team, which was provided with PPE, used the survey as an opportunity to distribute hand-washing buckets, soap, and informational leaflets on Covid-19 to local chiefs.

The results from the first round, which was nationally representative, showed that 60% of respondents could not prepare and store more than three days of food at a time, and only 12% could prepare food for a week or more, suggesting that if Sierra Leone had long lockdowns, many people might run out of food.

While many other countries, including neighboring Liberia, enforced weeks-long lockdowns, Sierra Leone decided to limit lockdowns to three days. Andrew Lavali, IGR’s Executive Director, says that the IGR-MIT GOV/LAB survey results were “instrumental in making that decision” to continue with three-day lockdowns.

The follow-up phone survey

Planning ahead for a remote follow-up

As Covid-19 began to spread, the research team decided that they would conduct the second round over the phone, even though many people had limited access to phones and cell service. To reach more of these people, the researchers gave away phones to 600 respondents and told them when they could expect a call during the next round, since the respondents might have to travel to an area with good service to receive the call.

Missing voices from the phone survey

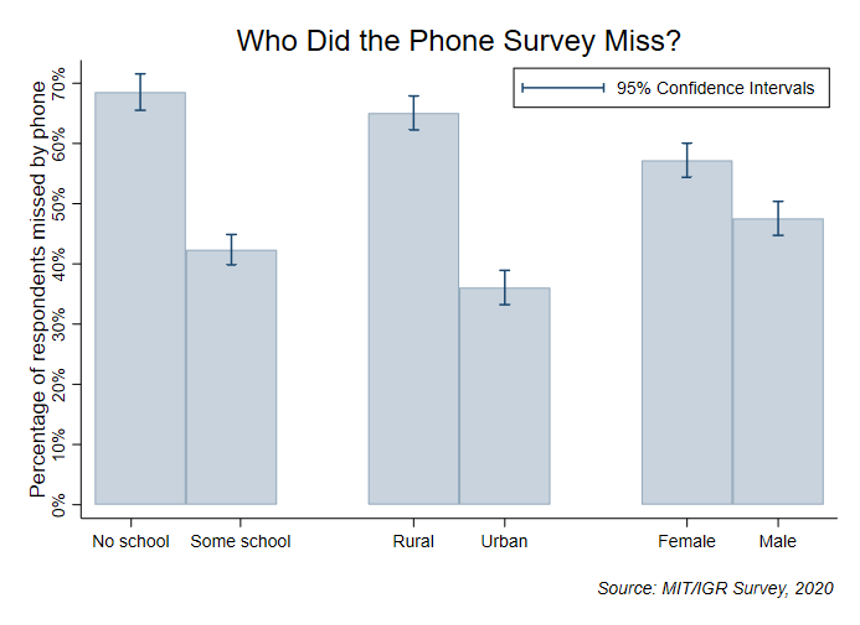

While the phone survey reached about half of the original respondents, a typical response rate for this type of survey, analysis by MIT GOV/LAB Research Affiliate Rodrigo Cordova-Ponce shows that the phone survey still undercounted some vulnerable groups, including people living in rural areas, as well as women and those with no schooling. People who went without food at least once in the week before the first survey were 7% less likely to be reached in the second round. Policy based on the phone survey alone might have not given enough weight to the needs of vulnerable people with little food.

The challenges with making the phone survey representative

Part of the reason why the phone survey didn’t reach as many at-risk people as hoped is that the survey team had only one-to-two-days to train enumerators and didn’t have time to check their data for accuracy, since they were trying to finish before the pandemic potentially spread more. As a result, some phone numbers were recorded incorrectly. Then, the phone survey took place later than anticipated. Fredline M’Cormack-Hale, Seton Hall University Associate Professor and IGR Research and Policy Director, said that after the scheduled window passed, people no longer knew when to expect the calls, so people in areas with poor service might not have been in an area with good service when the late calls came in.

Finding those missed by the phone survey

The fact that the phone survey undercounted certain groups is “perfectly logical and to be expected. Poorer people, rural people, women, these are often the populations that don’t have access to phones. There are just so many different reasons for their vulnerability,” says M’Cormack-Hale.

The research team could see that they weren’t reaching as many at-risk people via phone as they had hoped, and by the summer, the pandemic hadn’t hit Sierra Leone nearly as hard as other countries. So they followed up with a second round of in-person surveying in mid-August, during which enumerators continued to take safety precautions, including wearing masks and practicing social distancing. After this follow-up, the researchers had significantly more responses from people overlooked by the phone survey, including those struggling with food insecurity.

Lavali and M’Cormack-Hale both think that it will help in future surveys to verify phone numbers and stick to the schedule for calling back respondents. Rosenzweig also hypothesizes that checking in with respondents between survey rounds, rewarding people for responding to the phone survey, and providing respondents with solar phone chargers are all strategies that could make phone surveys more representative.

Ultimately, the goal is to make sure the survey includes people from vulnerable communities, so that new policies take into account their needs.

Enumerator Binta Jalloh (left) surveys a respondent in the Port Loko District, Sierra Leone.