The webcast recording is available online. Professor Tsai’s remarks starts at minute 22:00.

Experts and policymakers participated in “Trust in Pandemic Tech: Smartphone Apps for Participatory Response” hosted by the Responsible Data Foundation. The session centered on the MIT Program for Trusted Pandemic Technologies, which aims to help public health professionals overcome challenges by engaging citizens in digital solutions to support the pandemic response

As part of the keynote discussion, Congressman Bill Foster (D-IL) noted that “You need trusted people” to check “whether something nasty is snuck in [to the tech]”. Congressman Foster emphasized the need for deliberate construction of trust in the U.S. to deal with the pandemic, and that we “have to guard that trust carefully, there’s no substitute for that. Everyone needs to trust someone to do oversight”

Building trust won’t be easy

Assuming it’s possible to build pandemic tech that the public should trust (i.e., reliable, data-privacy protected), below are four highlights from Professor Tsai’s lightning talk on how to build trust given high levels of distrust in government, technology and society.

1. Trustworthy vs. trusted. There’s a difference between technology that should be trusted and will be trusted. Governments and companies tend to focus on using information and education campaigns to explain to the public why the technology is trustworthy. But in behavioral science we know that simply explaining why technology should be trusted doesn’t always have an impact on whether it is trusted.

2. Intentions matter. A key challenge is the difference in knowing something is capable of protecting privacy and believing that the purveyors of that technology have good intentions. It’s not that the public doesn’t understand why they should trust something, but rather that the public thinks governments and technologists lie about their intentions. Or if they aren’t lying, then maybe they don’t really care about the public good, that they have ulterior motives. The public trusts intentions.

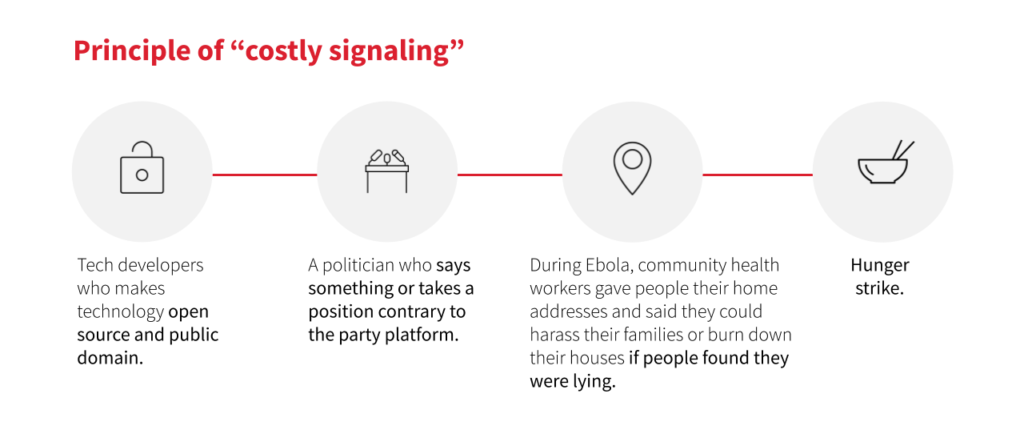

3. Costly signals for public good. How do you build trust in good intentions when there is distrust? Evidence from behavioral science suggests that when we want to build trust, we have to engage in costly signaling. That is, actions or behavior with potential consequences that put significant personal value on the line, to demonstrate to the public that governments or technologists are not motivated by our own self-interest.

Examples of costly signaling good intention in the public interest are technology developers that make technology open source. Or, citizens may be more likely to believe a politician who says something contrary to their party platform (some relevant research). Our research at the MIT Governance Lab on the Ebola epidemic showed that community health workers who gave people their home addresses and told them they could come harass their families if people found that they were lying (what we call “source accountability” in our research)—very costly signal to demonstrate the importance of following public health measures.

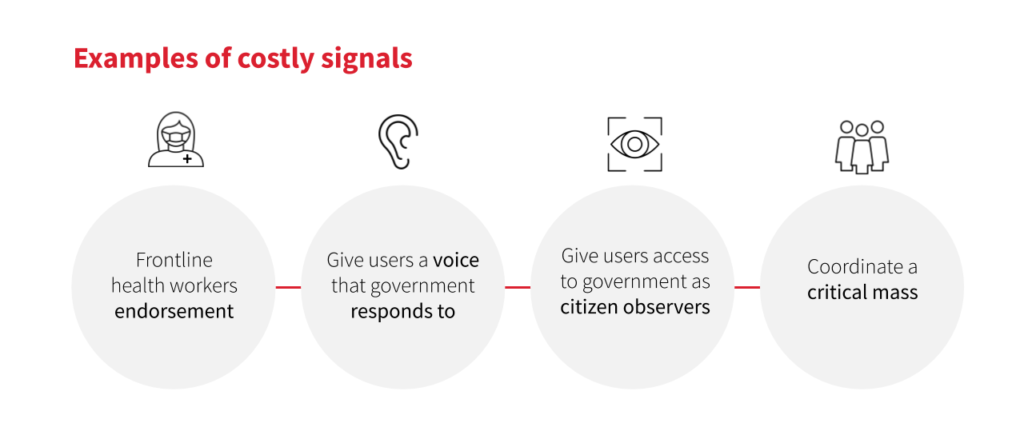

4. Costly signals for pandemic trust. How can costly signaling be applied to building trust in pandemic technology? Some examples: Getting frontline health workers who have put their lives on the line to endorse contact tracing efforts, manual or digital. State or city governments that enable app users to send feedback or provide input to the government Covid response, or even randomly give citizens access to the Covid response task force meetings as a citizen observer. These innovations have yet to be tested, and would need to be designed with a way for the government to respond so citizens know they are heard.

MIT GOV/LAB is working on a number Covid-19 research collaborations, with an emphasis on better understanding how to build public trust for public health interventions.

Illustration by Susy Tort.