In the spring of 2020, the MIT Governance Lab (MIT GOV/LAB) and MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab (CDDL) partnered with Sierra Leone’s Directorate of Science, Technology and Innovation (DSTI) and Africell, a wireless service provider, to measure the effectiveness of lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some countries have used mobility data, such as data from traffic sensors and GPS sensors in smartphones, to study how people travel during the pandemic, but this mobility data isn’t available in Sierra Leone. Instead, the research team used data from cellphone towers, which get pinged when someone nearby makes or receives a call or sends or receives an SMS message, to confirm that people did move around less during lockdowns. (More on these findings in this post).

Drawing on this work in Sierra Leone, MIT GOV/LAB and CDDL put together a technical guide, written by MIT GOV/LAB research associate Innocent Ndubuisi-Obi Jr., on how these cellphone tower data (“call detail records,” or CDRs) can be used to plan a response to a public health crisis. The guide includes lessons on how to securely access and store data, ensure its accuracy, clean and analyze it, and protect the privacy of the people behind the data.

For organizations and governments that might want to do this kind of mobility analysis but aren’t sure where to start, this guide can serve as a blueprint.

In the following conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, MIT GOV/LAB science writer Will Sullivan talks with Ndubuisi-Obi Jr. about how the researchers and Sierra Leone’s government collaborated to study the effect of lockdowns, how mobility data can shape policy, and ethical issues to consider when using this data.

Will: So the guide walks you through the steps for using CDR data. I imagine you need some advanced technical skills to do that sort of analysis, but who else can learn something from the guide?

Innocent: The intended audience is policymakers, researchers, and practitioners interested in using mobility analytics to supplement their work. The idea is that the main sections of the guide should be approachable to everyone, and then there are some other parts that go into a little more depth.

Will: And what might these groups learn?

Innocent: The guide demonstrates how CDRs can be a useful tool for informing policy when other mobility data is lacking. It can help groups understand whether this is analysis they want to engage in, particularly in a rapid-response scenario, and it shows the limitations of that analysis. It also gives an overview of what’s required to do the analysis. You’ll get a good idea of who the actors are, and what their main responsibilities are.

Will: It makes sense that a guide on doing this analysis would be helpful, since working with CDR data can be tricky. What were some of the challenges you faced with using this data in Sierra Leone?

Innocent: First of all, a CDR is only recorded when a subscriber makes or receives a phone call or a text message. If I only make or receive two calls in a day, it’s unlikely that those two records will usefully approximate my mobility.

Then there’s the issue of sparsity with tower distribution. If there are only five towers in a district, then at most there are only five unique points I can ping. And if I work in the same area I live, I’m just going to ping one or two towers, which doesn’t really tell me much about mobility. The majority of our CDRs showed people bouncing back and forth between two towers.

Also, the penetration of mobile phones is increasing, but it’s not that high. [According to a 2020 Afrobarometer survey, 75% of people in Sierra Leone own a cellphone.] People also share phones. So if you’re using CDRs to record the behavior of individuals, that data might not be correct.

Will: But you were still able to use this data to answer some questions about people’s movements during lockdowns. What did you find?

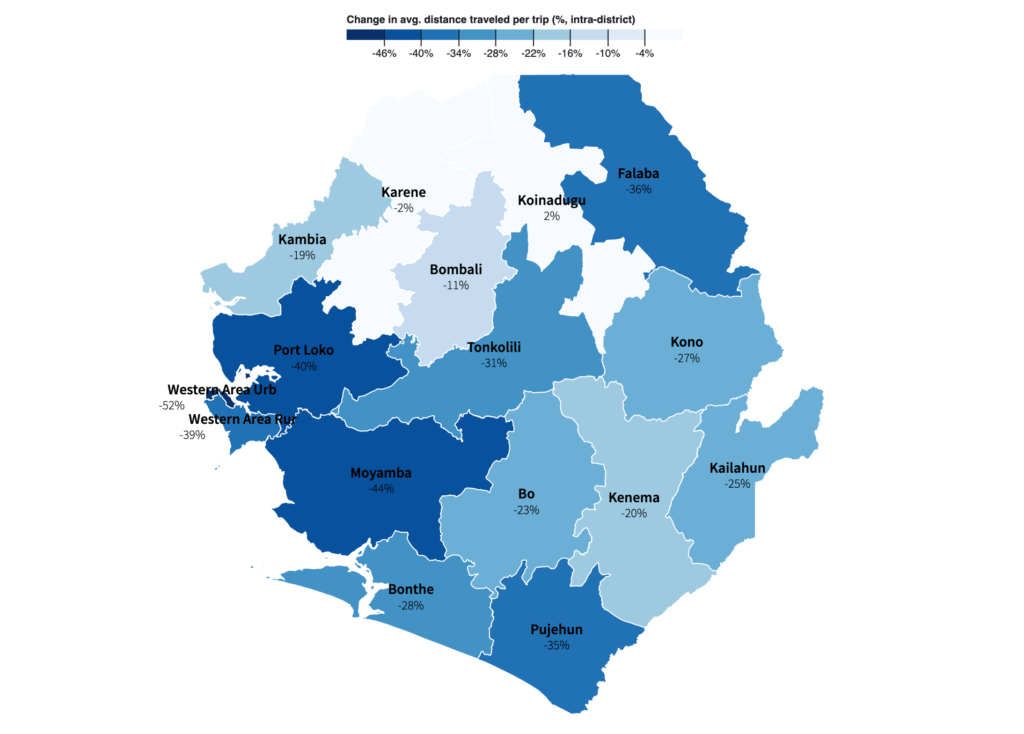

Innocent: We found that, on average, people did reduce their mobility between districts, and also within districts. We then tried to understand the effect of socio-economic factors, and found that the poorer the district, the less people’s mobility decreased, and found the same for places with smaller populations. Government officials can then see that lockdowns are effective at reducing travel and that poverty and other socio-economic factors need to be considered when developing policies.

Change in average distance traveled per trip within districts in Sierra Leone (MIT GOV/LAB and CDDL).

Will: I know with these mobility tracing tools (and this is something you talk about in the guide), privacy is a concern. What are some of the privacy issues related to CDR data, and what can researchers do to make sure they’re not violating people’s privacy?

Innocent: You don’t ever want to release data that will help identify someone. Before we get CDRs from our data partner, we make sure all personal information is removed, like someone’s phone number or address, or their gender or age.

And while CDRs don’t reveal a person’s actual location, just the towers they are close to, a record of a single person’s tower pings can still be used to re-identify that person. And even if you can’t identify an individual, you could identify a group of people with similar mobility patterns, like a group of farmers or healthcare workers.

So you have to make sure that data is securely stored. In the guide, we talk about some ways to store data and safely access it. Part of our-data sharing agreement in Sierra Leone was that we would only publicly share aggregated and anonymized statistics, which protects subscribers’ privacy.

Will: Since working with this data can put people’s privacy at risk, should we still be using it?

Innocent: I would rather not work with CDRs. But in the context of the developing world, there’s this understanding that without this data, there isn’t anything else that we could use to get at policy-relevant questions about mobility, like “are people complying with lockdown measures?”

But we know that relying on CDRs isn’t sustainable in the long run. We need fewer people touching CDRs. There’s some really great work happening with helping mobile network operators partner with NGOs and public sector organizations to do CDR analysis without giving them the data. Something MIT can do is support this kind of work.

Will: Tell me about your working relationship with government partners in Sierra Leone.

Innocent: We collaborated closely with government partners [DSTI], and their expertise guided our research. A main concern for them was, “how are we building capacity within Sierra Leone to do the same analysis?” So we offered a training on CDR analysis for partners and stakeholders.

When you’re working with CDR data, it’s important to work with your partners to make sure you know what’s happening on the ground. In the guide, I talk about the importance of making sure all the partners are at the table and actively asking questions — because if you don’t know the context, you might misinterpret the data. The guide’s not just about how to do the analysis. It also talks about how to communicate with partners, share findings in actionable ways, and build capacity within your government partners so they can reproduce this work.

Check out the guide here.

Freetown, Sierra Leone. Photo by Random Institute on Unsplash.