This Week in Social Science (TWISS) was created by Chris Grady and Levi Adelman as an adaptation of a USAID research newsletter. The aim of the newsletter is to simply and succinctly summarize the most recent academic research on a specific topic. You can see the original post here.

Citizenship and democratic responsibilities

Most public commentary, both popular and academic, is pessimistic about citizens and their capacity to fulfill their democratic obligations. But what does recent research say about the capacities (or lack thereof) of citizens?

An article out this week assesses whether citizens are competent enough to sustain democracy. It first identifies three responsibilities of democratic citizens: (1) reliably form beliefs based on factual knowledge, (2) hold politicians accountable for their actions, and (3) relate to fellow citizens as equals – even when they disagree. Let’s take each in turn.1

Can citizens hold factually accurate beliefs?

A common narrative is that citizens do not (and perhaps cannot) form beliefs based on factual information. Citizens know little about politics and interpret information to support their existing beliefs, which leads to widespread misinformation and the general incoherence of public opinion.

However, recent research suggests that the extent of public ignorance and the prevalence of misperceptions have been exaggerated. For example, a review of survey data found that incorrect coding of survey responses severely underestimated citizens’ political knowledge. Similarly, a recent article measuring misperceptions found that many “misperceptions” are actually people randomly guessing, not factually inaccurate beliefs.

Recent research is also more optimistic about citizens’ reactions to information they disagree with. Rather than cling to incorrect beliefs, people typically respond to factually correct information by adopting more accurate beliefs, irrespective of their prior opinions. This response to new information is true for respondents around the world.

This research shows that though citizens are not perfectly informed, they are more knowledgeable than previously assumed and tend to update their beliefs when presented with countervailing information.

Can citizens hold politicians accountable?

People may be able to hold factually-informed beliefs, but can they use those informed beliefs to hold politicians accountable, or are they easily manipulated by elites?

There is no doubt that political elites can influence their followers, but attempts by elites to manipulate political beliefs tend to fail or have vanishingly small effects. An exhaustive meta-analysis of 49 experiments about political campaigns – the strategic communications of political elites – showed that campaign communications do not effect who Americans vote for. Further, elites respond to citizens’ preferences. A study analyzing eighty-five years of data on public opinion in US states showed that state policy comes to resemble the wishes of its citizens.

Still, concerns about accountability are not unwarranted. Partisans interpret the same facts quite differently, and these interpretations drive their views and behavior. For example, one experiment gave participants positive or negative articles about the US economy under then-President Obama. All participants accurately updated their views about the state of the economy, but were biased in assigning credit or blame. If the economy was going well, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to credit President Obama; and if the economy was going poorly, Republicans were more likely than Democrats to blame President Obama.

This research suggests that people are neither gullible nor easily misled by political elites, but that partisanship colors how we reward and punish politicians.

Can citizens relate to each other as equals?

The last concern is that partisan polarization prevents citizens from meaningful dialogue, and can even lead them to condone violence. Polarization has increased dramatically in many democratic societies, and this certainly affects attitudes and behaviors. For example, the proportion of Americans who say they would be upset if a child of theirs married a member of the opposite party increased sixfold between 1960 and 2010.

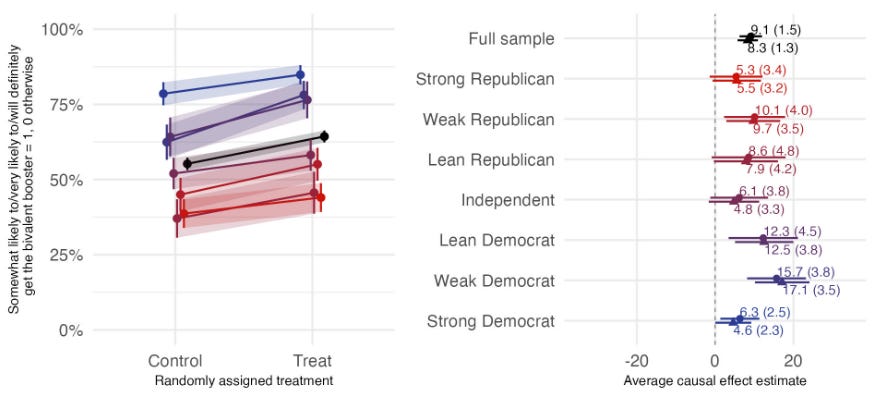

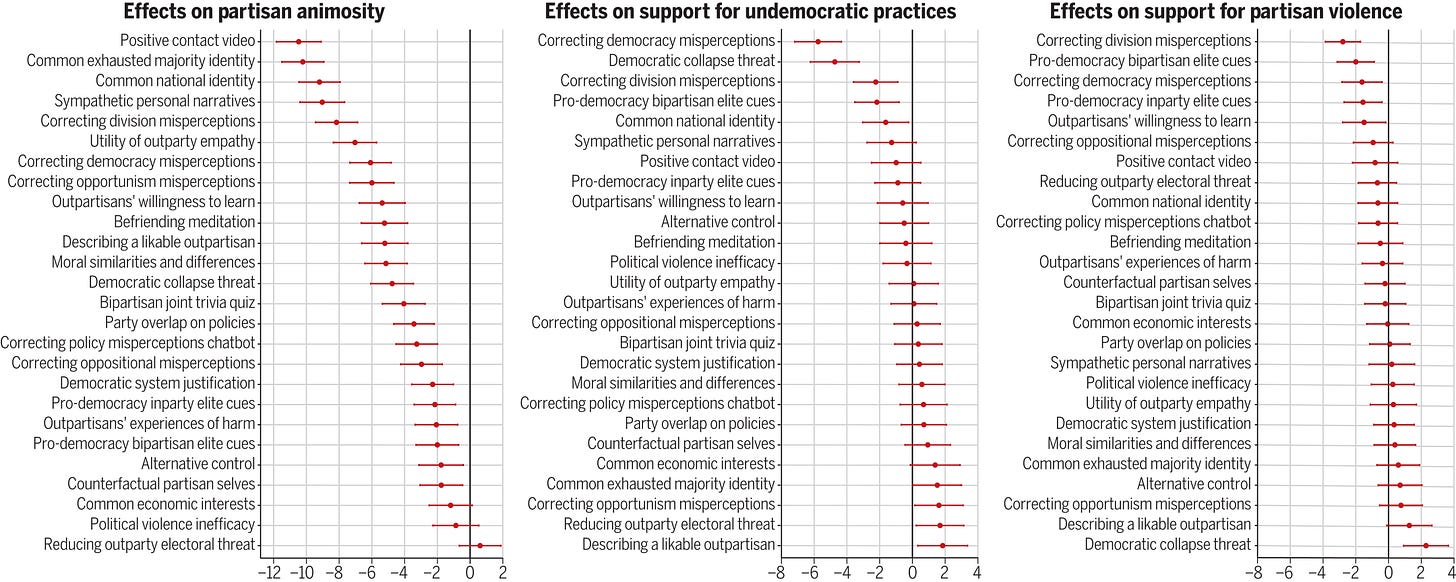

But polarization is not intractable. Recent studies have offered a wide range of interventions that successfully weaken polarization. And although political violence is alluring to a small percentage of citizens, the vast majority of citizens uniformly condemn political violence.

This research shows that partisan animosity can be reduced by interventions as simple as correcting misperceptions about the other side, and that our current levels of partisan animosity have not driven us to wish harm upon our political opponents.

Takeaway: Citizens are not perfect, but nor are we hopeless. We tend to hold reasonable preferences, and over time politicians reflect those preferences. And we do not reject democratic procedures in favor of violence. We are competent enough for democracy.

After all this, I am left with a final question: why are we prone to believing that everyone else is ignorant, biased, and prone to violence? But that is a question for another time.

Photo by Elimende Inagella on Unsplash.